你不知道的英镑纸币防伪密码 - BBC克里斯·巴拉尼克(Chris Baraniuk)(2023年7月9日)

一台全新的施乐彩色复印机刚被送到剑桥的一家工业实验室中。这是21世纪初,这台新发明的精巧装置到来的消息马上就在当地传开了。这其中就包括当时还在攻读博士学位的计算机科学家马库斯·库恩(Markus Kuhn)。没多久,库恩就想出了一个测试这台复印机性能的最佳方式。

库恩把一张20英镑的钞票放在玻璃表面进行扫描。他盖上盖子,按下复印按钮,静静等待。然而托盘中出现的不是钞票的彩色复印件,而是一段以不同语言显示的通知:复印纸币是违法行为。

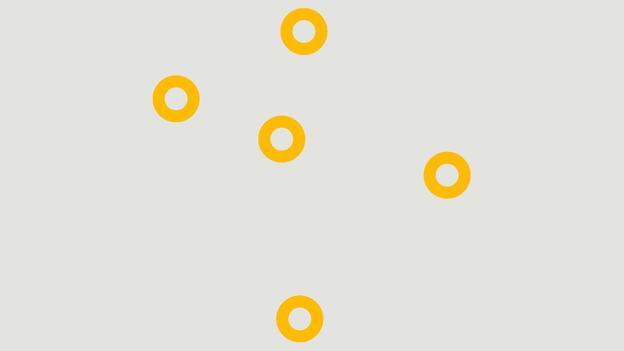

重复出现的星座防伪标记

这让人颇感意外。复印机是怎么知道它复印的东西是什么的呢?“那时欧元纸币刚刚发行,”库恩说道,“我的钱包里就有一张10欧元的纸币。在10欧纸币上,我注意到由这些小圆圈构成的格外明显的图案。我盯着它们看了一会然后发现这些图案中的星座状标记重复出现。”

库恩又观察了20英镑的纸币。它也有那样的图案,不过这次它被掩藏在纸币正面印刷着的一幅乐谱图案中。所以,无论是英镑还是欧元的纸币的正反面都印有一幅由五个圆圈构成的图案。很快他发现,其他国家的纸币也印有同样的图案。然而,不同国家的纸币、乃至同一币种中不同面额的钞票都拥有不同的颜色,图案出现的方位也不尽相同,彩色复印机又是如何每次都能识别出这些图案的呢?

库恩开始了调查。最初,他在一张白纸上单独画出这一图案,打印它并试图复印它。在黑白模式中,复印机乖乖复印了图案。但当库恩给圆圈上了色,这次复印出来的却是防假冒信息。他说:“这似乎是因为电路需要以彩色通路、而非黑白通路呈现的圆圈。”因为五个圆圈所模仿的是猎户星座,库恩将这一图案命名为圆圈星座防伪标记。

虽然库恩认为颜色是防伪码的关键组成的部分之一,其他人则认为复印机也会侦测五个圆圈之间的特定距离。库恩一直没能独立验证这一理论。

复印机和扫描机如何识别防伪图案的确切方式仍然是个谜。不过,一份由印度马哈拉施特拉邦银行(Bank of Maharashtra)颁布的文件给我们提供了一些线索。从该文件可以知道,存在着一种机制用来侦测和肉眼看到的颜色不同的圆圈。文件写道:“复印的纸币上的亮色部分会呈现出和真实钞票不同的颜色。”

要知晓防伪图案的运作原理是很困难的。从银行官员到设备制造商,没有人愿意谈论这个问题。英格兰银行甚至从未公开谈论过圆圈星座防伪图案的存在。相反,纸币部主任维多利亚·克莱兰(Victoria Cleland)在一次采访中称,银行希望伪造纸币越难越好。

是谁最先想出使用圆圈星座防伪标记?虽然他们拒绝为本文发表评论,2005年印度储备银行刊发的一篇新闻通稿却将一家名为欧姆龙(Omron)的日本公司和这一图案联系到了一起。今年1月,一篇由退休的印度政府官员N·R·扎亚拉曼(Jayaraman)所写的博客旧事重提,宣称被他称为欧姆龙圆圈的防伪设计自1996年起就使用在世界各国的纸币上。他的博客还宣称:“欧姆龙圆圈标记的设计和尺寸和该公司通过SSG-2方式处理过的底片胶卷一模一样。公司自己提供的这种胶卷不能以任何方式进行改造,否则防复印功能将失效。”

“甜甜圈”防伪保障

看来SSG-2指的是将防伪图案转印在纸币上的方法。然而在一封电子邮件中,扎亚拉曼又说他并不知道这一过程中的确切步骤。

一长串公共专利则进一步表明事实上欧姆龙就是站在圆圈星座防伪技术背后的那家公司。1995年提交的一份专利称它可以“识别印刷在图像数据上的、按特定空间关系排布的标记,例如纸币或可流通证券。”虽然缺失了位于中央的圆圈,这份专利所附的图片中呈现的图案和圆圈星座防伪图案如出一辙。

有一个人能带我们一探图案的奥秘,他就是史蒂夫·凯西(Steve Casey),英诺薄膜公司(Innovia Films)的市场总监。英诺生产印刷纸币的原料纸片。“这些环在我们行业被叫做‘甜甜圈’”,他解释道,“它是数字时代中纸币最早采用的安全措施之一。”

当被问及施乐复印机和扫描仪是否能够识别圆圈星座防伪图案时,一位施乐公司发言人在电子邮件中回答道:“和其他影像公司一道,施乐同全球执法机构和中央银行假币防治组(Central Bank Counterfeit Deterrence Group)(一个由32家中央银行和印钞部门组成的集团)一同协商,来评估纸币所受的威胁并促进和支持防伪技术的使用。为防治特定的犯罪行为,检测造假的技术都是标准化的。”不过,公司又补充道:“施乐对使用的范围不作评论。”

即使我们能把圆圈星座防伪技术调查得水落石出,也不足以完全解开谜题:纸币上还有其他隐藏起来的防伪码。英诺薄膜公司的凯西说,纸币中还有“第三级”防伪标记,它甚至比圆圈星座图案更为隐秘。“第三级防伪标记不是可以谈论的话题。除了中央银行,没人知道它们的存在,”他说,“他们的高速验钞机被校正用来检测这个标记,于是验钞机可以很明确地认定这是不是一张假币。”

事实上,英格兰银行的克莱兰说,“大规模现金处理机构”所使用的钞票分拣机是伪钞的最大来源:这些机器分配并收集来自诸如零售商、银行和自动取款机的钞票。

其他防伪码可以对诸如Adobe公司旗下的Photoshop等图片编辑软件产生影响,防止用户编辑纸钞的图像。库恩昔日的学生,计算机科学家史蒂芬·默多克(Steven Murdoch)已经调查了这一点。默多克认为图片编辑程序检测的是圆圈星座防伪标记之外的东西:肉眼不可见的数字水印。DMRC公司(Digimarc)被认为是这项技术的创始人,公司拥有的一项专利解释了它的工作原理。DMRC公司在这一领域还拥有其他有趣的专利,比如有一项专利就描述了如何秘密记录计算机用户是否用照片编辑软件处理过纸币的图像。执法人员可以在获取疑犯的电脑后收回这些数据。

我们并不知道是否有商业软件程序加载了这样的技术。DMRC公司同样拒绝对本文发表评论。但是中央银行假币防治组的组长皮埃尔·拉佩斯(Pierre Laprise)表示中央银行伪造防治组并没有开发一种能记录非法使用的程序。“因为隐私问题,我们并不跟踪动向。”

不过,拉佩斯承认中央银行伪造防治组确实开发了防止复印和图片编辑的技术,但他拒绝讨论任何相关细节。尽管没有提供任何细节,拉佩斯表示他的防治组在这一领域取得的效果是十分显著的。“这确实十分有效,”他评论道,“我们能否完全阻止伪造?也许不能,但我们致力于减少伪造,而这么多年我们也确实有效控制了伪造问题。”

也许我们永远不会知道这些防假冒技术如何生效的全部细节,或这些技术究竟被用在那里。但正如库恩所言,幸好我们不知道。人们试着使用彩色复印机来复制纸币是一件不可避免的事情。“我认为这是一件显而易见的事情,”他说道,“复印机制造商们显然也是这么认为的。”

而史蒂芬·凯西表示,把伪造活动限制在专门的、更易于追踪的单元要好得多,不然会有许许多多的业余爱好者试图一展身手。“中央银行最不想要的就是遍布全国的数以百计的造假者。他们不希望人们能够很容易的设立一个假钞复印厂之后即刻换一个地方接着干。”

“如果这样的话,那就非常难以追踪了,” 凯西最后说。

(责编:友义)

The secret codes of British banknotes - By Chris Baraniuk

A brand-new Xerox colour photocopier had just arrived at one of Cambridge’s industrial labs. It was the early 2000s, and word of the new-fangled contraption quickly got around – including to computer scientist Markus Kuhn, then a PhD student. It didn’t take him long to decide on the best way to test its abilities. “We were students,” he recalls with a laugh. “We went straight for the banknotes.” (Don’t try this at home – the photocopying of banknotes, in the UK and in other countries, is illegal).

Kuhn placed a British £20 note on the glass surface to scan. He closed the lid, pressed the copy button and waited. The copier whirred. But no colour reproduction of the note appeared in the tray. Instead came a message printed in various languages – explaining that copying banknotes was illegal.

Recurring constellation

This was a surprise. How did the copier know what it was being asked to print? “The euro banknotes had just come out,” says Kuhn, “and I had a 10-euro banknote in my wallet. On the 10-euro banknote, I spotted this particularly obvious pattern of little circles. I stared at it for a while and I saw that the constellation inside this pattern was recurring.”

Kuhn looked again at the £20 note. The pattern was there, too, but on the front of the note it was hidden in a motif of printed music: the circles were printed as the heads of the musical notes. So a recurring pattern of five circles existed on sterling and euro banknotes, on both the front and back. Other currencies around the world, it soon emerged, were printed with the same pattern. But since different notes varied their colours and orientations of the patterns, even across different denominations of the same currency, how did colour photocopiers pick out the pattern each time?

Kuhn began to investigate. At first, he drew the pattern in isolation on a blank piece of paper, printed it and tried to photocopy it. When it was a black-and-white pattern, the photocopier reproduced it without quibbling. But when Kuhn coloured in the circles, the anti-counterfeiting message was churned out instead. “There appears to be some circuitry that requires the circles to be present in a colour channel, not in a black-and-white channel,” he says. Kuhn named the pattern the EURion Constellation after the astronomical constellation of Orion, which it resembles.

Although Kuhn thinks colours are one key part of the code, others have suggested that photocopiers are also looking for specific distances between the five circles. Kuhn has not been able to independently verify this theory.

The precise means by which copiers and scanners recognise the pattern remain a mystery. One clue, though, comes from a document published by India’s Bank of Maharashtra, which suggests that there is some kind of mechanism for detecting the circles in a different colour to that seen by the naked eye. “The highlighted portion […] in the banknote when photocopied will exhibit a different colour distinct from genuine banknote,” the document reads.

Getting confirmation of how the pattern works – or even whether it does what researchers think it does – is difficult. No one, from bank officials to equipment manufacturers, wants to talk about it. The Bank of England has never commented publicly on the existence of the so-called EURion Constellation. Instead, in an interview, director of banknotes Victoria Cleland explained that the bank has an interest in making counterfeiting as difficult as possible. “If you get a £20 counterfeit note today, it’s worth absolutely nothing,” she explains. “You’ll be £20 out of pocket. So on an individual by individual basis, it’s bad news – and people could lose confidence in the cash they’re using.”

Who came up with the EURion Constellation in the first place? Although they declined to comment for this article, a Japanese firm called Omron was linked to the pattern in a 2005 press release published by the Reserve Bank of India. In January of this year, a blog post apparently written by a retired Indian government official named N R Jayaraman stated that the design, which he called the Omron pattern, has been used on banknotes around the world since 1996. His blog post also stated: “The design and size of the Omron mark shall be as per the master film provided by the SSG-2, the film supplied by the firm itself and should not be altered in any manner, lest the anti-copying feature will fail to work.”

Security ‘doughnuts’

It seems that SSG-2 refers to the method by which the pattern is transferred to banknote paper during printing. In an email, however, Jayaraman said that the specific machinations of the process are not known to him.

A string of public patents provide further evidence that Omron is indeed behind the EURion Constellation. This one, filed in 1995, states that “marks are detected which are arranged in a given spatial relationship in image data printed on, for example, bank notes or negotiable securities.” An image attached to the patent shows a pattern that is conspicuously similar to the EURion Constellation, albeit with the central circle missing.

One person able to shed some light on the pattern is Steve Casey, marketing director for Innovia Films, which manufactures sheets of material onto which banknotes may be printed. “The rings are called ‘doughnuts’ in the industry”, he explains. “It’s one of the first security features that was ever developed for banknotes in the digital era.”

When asked to confirm whether Xerox photocopiers and scanners have been designed to recognise the EURion pattern, a Xerox spokesperson said in an email that “Xerox, along with other imaging companies, consults with the global law enforcement and the Central Bank Counterfeit Deterrence Group, a consortium of 32 banks and note printing authorities, to assess threats to currency and to promote and support the use of anti-counterfeiting technologies. To provide protection against specific criminal behaviour, technology to detect counterfeiting is standardised.” However, they added: “Xerox does not comment on the scope of deployment.”

Even if it were possible to get to the bottom of the EURion Constellation, there’s another piece of the puzzle: there are other hidden codes on banknotes, too. Innovia Films’ Casey says that there are also ‘Level 3’ features within banknotes that are even more secret than the EURion Constellation. “Level 3 features aren’t discussed. No one knows about them except a central bank,” he says. “That is something that their high speed note-sorting machines will be calibrated to read and they will be able to definitively identify whether something is a counterfeit note or not.”

Indeed, the Bank of England’s Cleland says the greatest source of counterfeit notes are the sorting machines used by “wholesale cash handlers” – those who distribute cash to and from retailers, banks and ATMs, for example.

Other codes may affect photo editing software like Adobe Photoshop, preventing users from editing images of banknotes. This has been investigated by Steven Murdoch, a computer scientist and former student of Kuhn’s. Murdoch believes image editing programmes are detecting something other than the EURion Constellation: a digital watermark invisible to humans. A method for doing this is described in a patent by Digimarc, the company believed to have developed the technique. Digimarc has also filed other interesting patents in this area, such as one which describes a method for secretly recording whether a computer user has been working with images of banknotes in a photo editing programme. Law enforcement agents could later retrieve such data after seizing a suspect's computer.

It’s not known which, if any, commercial software programmes include such a technology. Digimarc also refused to comment for this article. But Pierre Laprise, director of the Central Bank Counterfeit Deterrence Group, says that CBCDG has not developed a method of recording illicit use. “We do not track,” he says, “because of the privacy issues.”

Laprise did, however, confirm that the CBCDG has indeed developed technologies to prevent photocopying and image editing – but he would not discuss any of the details. Whatever the specifics, Laprise says his group’s efforts in the area have been highly successful. “It’s definitely been effective,” he comments. “Will we be ever able to stop counterfeiting? Probably not, but we’re working at reducing it, and it’s been pretty well contained over the years.”

We may never know the full details of how technologies intended to deter counterfeiting work, or where they are used. But as Kuhn says, perhaps it’s just as well. That people would try to use colour photocopiers to reprint banknotes was, of course, inevitable. “I think it’s a fairly obvious thing to do,” he says, “and the manufacturer evidently thought so.”

And Steve Casey says it’s ultimately better to restrict counterfeiting to dedicated and more easily traceable cells, rather than many pockets of amateurs all having a go. “What a central bank doesn’t want is hundreds of counterfeiters across the country. They don’t want people able to set up their little photocopying operation and then move on.

“That,” he adds, “would be very hard to trace.”