HIV病毒和艾滋病从哪里来的?

BBC双语科林·巴拉斯(Colin Barras)(2023年12月6日)

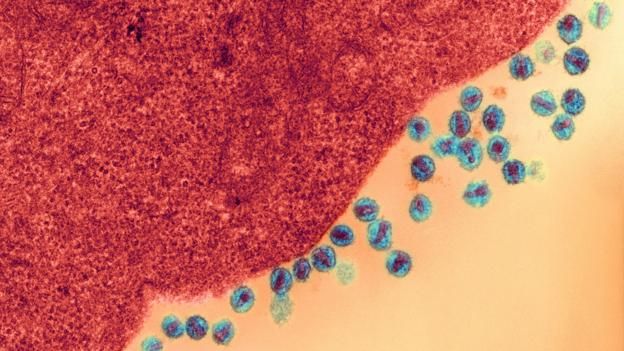

HIV微粒正在感染细胞(图片来源:Animated Healthcare Ltd/SPL)

当美国医务工作者35年前第一次发现艾滋病时,不难想象他们内心所面临的困惑和恐惧。这种病毒会侵蚀健康人体原本强大的免疫系统,导致他们身体虚弱,不堪一击。然而,我们对它的起源似乎完全摸不着踪迹。

如今,我们对人类免疫缺陷病毒(HIV,即艾滋病病毒)在全球广泛流行的方式和原因已经有了很多了解。意料之中的是,性工作者不经意地在其中扮演了重要角色。但国际贸易的发展、殖民主义的崩溃以及20世纪的社会政治变革所扮演的角色同样不容忽视。

当然,HIV并非真的没有来源。它很有可能源自一种在非洲中西部感染猴子和猩猩的病毒。

在那里,它通过一些偶然的机会跨越了物种的界限,感染了人类,原因很有可能是人类食用了受到感染的丛林肉所致。例如,有些人携带的HIV病毒版本与白颈白眉猴身上发现的病毒很相似。但来自猴子的HIV尚未成为一个全球性问题。

猴免疫缺陷病毒(SIV)会感染猴子(图片来源:Science Picture Co/SPL)

与猴子相比,我们和猩猩的基因更加接近,例如大猩猩和黑猩猩。但即便是当HIV从这些猩猩传播给人类之后,也未必会演变成影响广泛的健康问题。

源自猩猩的HIV通常属于HIV-1,其中有一个名叫HIV-1的O组,而这种病毒的人类感染者主要集中于西非。

“这种HIV似乎只是充分利用了一系列事件。”

事实上,只有一种HIV在感染人类之后得到了广泛传播。这个名为HIV-1的M组很可能源自黑猩猩。超过90%的HIV感染者都属于M组。这便引发了一个重要问题:HIV-1M组究竟有何特别之处?

2014年发布的一项研究给出了令人意外的结果:M组或许并无任何特别之处。

它的传染性并不突出,这一点或许有些出人意料。相反,这种HIV只是充分利用了一系列事件。“促使它快速传播的是生态因素,而非进化因素。”英国牛津大学的努诺·法利亚(Nuno Faria)说。

法利亚和他的同事从中非约800名艾滋病感染者身上收集了各种HIV的基因组,并借此绘制了一份HIV系谱图。

“第一个HIV-1M组感染者可能是在20世纪60年代感染这种病毒的。”

猴免疫缺陷病毒(图片来源:Sriram Subramaniam/National Cancer Institute/SPL)

基因组发生新突变的速度非常稳定,所以只要对比两个基因组序列,并计算它们之间的差异,便可了解这两个基因组上一次来自共同的祖先是在什么时候。这项技术已经得到广泛的应用,例如,正是借助这项技术,才断定我们与黑猩猩的共同祖先至少生活在700万年前。

“HIV等RNA病毒的进化速度大约比人类DNA快了100万倍。”法利亚说。这意味着HIV的“分子钟”运转速度的确非常快。

法利亚和他的同事发现,它的运转速度极快,以至于所有的HIV基因组都来自100多年前的一个共同祖先。HIV-1M组的流行很可能是从20世纪20年代开始的。

随后,该团队又展开了更加深入的研究。因为他们知道每个HIV样本是从哪里搜集而来的,所以可以将这些病毒的源头定位到具体的城市:金沙萨,刚果民主共和国现在的首都。

研究人员现在已经调整了方法。他们转而通过历史记录来研究,为什么20世纪20年代在一个非洲城市的HIV感染会最终引发一场席卷全球的大流行。

很快,这一系列事件的发展脉络就逐渐清晰起来。

“到了20世纪60年代,HIV爆发的一切条件都已经具备。”

20世纪20年代,刚果民主共和国还是比利时殖民地,而金萨沙(当时的名字是利奥波德维尔)才刚刚成为首都。那里成为了许多年轻男性的淘金圣地,也聚集了许多性工作者。于是,HIV病毒便在人群中迅速传播开来。

一个被HIV感染的细胞(图片来源:Sebastian Kaulitzki/SPL)

这种病毒并没有局限在金萨沙。研究人员发现,在20世纪20年代,这个比属刚果的首都是与外界联系最为紧密的非洲城市之一。于是,HIV病毒充分利用了每年可以运送数十万旅客且覆盖广泛的铁路网络,在短短20年间传播到900英里(1500公里)之外的其他城市。

到了20世纪60年代,HIV爆发的一切条件都已经具备。

那个10年的开端还发生了另外一个变化。

比属刚果获得独立,并为海地等其他法语地区提供了充裕的就业机会。当这些年轻的海地人几年后回到家乡时,也把HIV-1M组(B亚型)一同带到了大西洋西岸。

它于20世纪70年代来到美国,当时正值性解放和同性恋运动的兴起,使得纽约和旧金山等大都市的男同性恋者成为了焦点。于是,HIV再次利用了当时的社会政治环境在美国和欧洲快速传播。

“倘若身处相似的生态环境,相信其他的亚型也会像B亚型这样快速传播。”法利亚说。

HIV正在感染一个细胞(图片来源:Credit: Ami Images/Dartmouth College - Louisa Howard/SPL)

但HIV的传播故事并未就此结束。

例如,HIV曾于2023年在美国印第安纳州大范围爆发,主要与毒品注射有关。哈佛大学公共卫生学院的约纳坦·格莱德(Yonatan Grad)表示,美国疾病控制和预防中心一直在分析HIV的基因序列,以及感染的地点及时间数据。“这些数据有助于了解病毒爆发的程度,并将进一步帮助我们了解在什么时候进行公共卫生干预才能起到效果。”

这种分析方法也适用于其他病原体。2014年,格莱德和他的同事马克·林普西奇(Marc Lipsitch)发布了一份研究报告,对整个美国的抗药淋病分布情况展开了调查。

“由于我们拥有不同时间、不同城市、不同性取向人群的基因组序列样本,所以便可呈现这种病毒在整个国家的分布情况。”林普西奇说。

另外,他们还证实,抗药淋病主要存在于曾经有过同性性行为的男性身上。这可以促使政府加强对高危人群的筛查,从而降低这种疾病进一步传播的概率。

换句话说,透过人类社会这个棱镜来研究HIV和淋病等病原体,才能起到真正的效果。

(责编:友义)

We know the city where HIV first emerged

By Colin Barras,6 December 2024

It is easy to see why AIDS seemed so mysterious and frightening when US medics first encountered it 35 years ago. The condition robbed young, healthy people of their strong immune system, leaving them weak and vulnerable. And it seemed to come out of nowhere.

Today we know much more how and why HIV – the virus that leads to AIDS – has become a global pandemic. Unsurprisingly, sex workers unwittingly played a part. But no less important were the roles of trade, the collapse of colonialism, and 20th Century sociopolitical reform.

HIV did not really appear out of nowhere, of course. It probably began as a virus affecting monkeys and apes in west central Africa.

From there it jumped species into humans on several occasions, perhaps because people ate infected bushmeat. Some people carry a version of HIV closely related to that seen in sooty mangabey monkeys, for instance. But HIV that came from monkeys has not become a global problem.

It seems that this form of HIV simply took advantage of events

We are more closely related to apes, like gorillas and chimpanzees, than we are to monkeys. But even when HIV has passed into human populations from these apes, it has not necessarily turned into a widespread health issue.

HIV originating from apes typically belongs to a type of virus called HIV-1. One is called HIV-1 group O, and human cases are largely confined to west Africa.

In fact, only one form of HIV has spread far and wide after jumping to humans. This version, which probably originated from chimpanzees, is called HIV-1 group M (for "major"). More than 90% of HIV infections belong in group M. Which raises an obvious question: what's so special about HIV-1 group M?

A study published in 2014 suggests a surprising answer: there might be nothing particularly special about group M.

It is not especially infectious, as you might expect. Instead, it seems that this form of HIV simply took advantage of events. "Ecological rather than evolutionary factors drove its rapid spread," says Nuno Faria at the University of Oxford in the UK.

Faria and his colleagues built a family tree of HIV, by looking at a diverse array of HIV genomes collected from about 800 infected people from central Africa.

The very first person to be infected with HIV-1 group M probably picked up the virus in the 1920s

Genomes pick up new mutations at a fairly steady rate, so by comparing two genome sequences and counting the differences they could work out when the two last shared a common ancestor. This technique is widely used, for example to establish that our common ancestor with chimpanzees lived at least 7 million years ago.

"RNA viruses such as HIV evolve approximately 1 million times faster than human DNA," says Faria. This means the HIV "molecular clock" ticks very fast indeed.

It ticks so fast, Faria and his colleagues found that the HIV genomes all shared a common ancestor that existed no more than 100 years ago. The HIV-1 group M pandemic probably first began in the 1920s.

Then the team went further. Because they knew where each of the HIV samples had been collected, they could place the origin of the pandemic in a specific city: Kinshasa, now the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

At this point, the researchers changed tack. They turned to historical records to work out why HIV infections in an African city in the 1920s could ultimately spark a pandemic.

A likely sequence of events quickly became obvious.

Everything was in place for an explosion in infection rates in the 1960s

In the 1920s, DR Congo was a Belgian colony and Kinshasa – then known as Leopoldville – had just been made the capital. The city became a very attractive destination for young working men seeking their fortunes, and therefore also for sex workers. The virus spread quickly through the population.

It did not remain confined to the city. The researchers discovered that the capital of the Belgian Congo was, in the 1920s, one of the best connected cities in Africa. Taking full advantage of an extensive rail network used by hundreds of thousands of people each year, the virus spread to cities 900 miles (1500km) away in just 20 years.

Everything was in place for an explosion in infection rates in the 1960s.

The beginning of that decade brought another change.

The story of the spread of HIV is not over yet

Belgian Congo gained its independence, and became an attractive source of employment to French speakers elsewhere in the world, including Haiti. When these young Haitians returned home a few years later they took a particular form of HIV-1 group M, called "subtype B", to the western side of the Atlantic.

It arrived in the US in the 1970s, just as sexual liberation and homophobic attitudes were leading to concentrations of gay men in cosmopolitan cities like New York and San Francisco. Once more, HIV took advantage of the sociopolitical situation to spread quickly through the US and Europe.

"There is no reason to believe that other subtypes would not have spread as quickly as subtype B, given similar ecological circumstances," says Faria.

The story of the spread of HIV is not over yet.

For instance, in 2015 there was an outbreak in the US state of Indiana, associated with drug injecting.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been analyzing the HIV genome sequences and data about location and time of infection, says Yonatan Grad at the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts. "These data help to understand the extent of the outbreak, and will further help to understand when public health interventions have worked."

This approach can work for other pathogens. In 2014, Grad and his colleague Marc Lipsitch published an investigation into the spread of drug-resistant gonorrhoea across the US.

"Because we had representative sequences from individuals in different cities at different times and with different sexual orientations, we could show the spread was from the west of the country to the east," says Lipsitch.

What's more, they could confirm that the drug-resistant form of gonorrhoea appeared to have circulated predominantly in men who have sex with men. That could prompt increased screening in these at-risk populations, in an effort to reduce further spread.

In other words, there is real power to studying pathogens like HIV and gonorrhoea through the prism of human society.