通往喜马拉雅山谷的危险公路(图文)

BBC希曼舒·哈格塔(Himanshu Khagta)(2016年4月30日)

印度旁吉至基斯赫特瓦尔(Pangi via Kishtwar)公路(图片来源:图片来源:Himanshu Khagta)

被穿越印度的一条叹为观止而又险象环生的公路所吸引,我们五个人挤进一辆车里。经基斯赫特瓦尔至旁吉(Pangi via Kishtwar)公路穿过两个偏远地区——查谟(Jammu)和克什米尔(Kashmir),当大雪阻断常规路线(经 Saach Pass),它就成为藏身于西喜马拉雅山脉比尔本贾尔岭(Pir Panjal Range)和赞斯卡山(Zanskar Range)之间的神秘的旁吉(Pangi)山谷通往外界的必经之路。

11 月的天气通常反复无常。大雪会让旁吉山谷完全与世隔绝长达数月,但我们还是决定踏上长途跋涉的征程。从印度北部不规则延伸的商业城市昌迪加尔(Chandigarh)一条最好的六车道公路出发,道路渐渐变窄,我们最终踏上为期两天的上坡路,这里之前曾经是山间小路。现在几乎是一条一车道的泥泞小路了,也就仅仅几年前,这条通道才出现在山腰。

据当地传说,逃离莫卧儿王朝入侵后,昌巴(Chamba)人就定居在这个隐蔽的旁吉山谷。显贵的家庭都会将妇女儿童送到旁吉,过上祥和宁静的生活。随后在 16 世纪,旁吉山谷由昌巴王国(Kingdom of Chamba)统治,派往这里的官员都会得到丧葬补助,因为预料他们永远不会返回家乡。另有传说称,昌巴国王会把罪犯发配到旁吉山谷服无期徒刑。

通往神秘的旁吉山谷的公路岌岌可危(图片来源:Himanshu Khagta)

旁吉至基斯赫特瓦尔公路刚好穿过山脉的岩脊,大部分宽度仅可容一辆小车通过。不过,有时候勇气可嘉的公交车和卡车司机也会在这条路上往来。如果有两辆小汽车在路上相向而行,其中一辆车的司机就必须小心倒车几百米开外,直到找到合适的通行点。沿着这条公路,悬崖峭壁直上山顶,然后又直下数千米,抵达碎石遍地的杰纳布河岸边。公路上岩石嶙峋,地势险峻,我们花了 4 小时才走了 30 公里路程。

一路上我们也遇到当地人,但他们对这种险峻的道路和周围环境都已经习以为常。原住民的后代旁吉人(Pangwal)还沿着公路边建起小农场。海拔较高地区的伯特(Bhot)人说藏语,大多数以畜牧为生。为了在恶劣的环境中生存,他们腌制肉类,存储大麦,还酿造一种在当地被称为“patru”或“rakh”的烈酒。冬季,整个山谷会被白雪吞没,是当地人最难熬的日子。通过公路抵达昌巴需要两天时间,在需要医疗急救时,政府会安排直升机为民众服务。

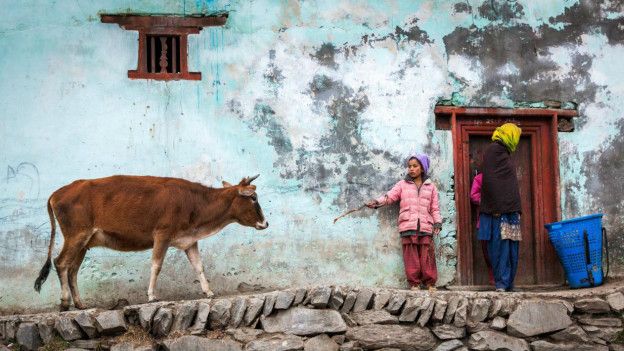

当地人沿着公路边建起小农场(图片来源:Himanshu Khagta)

在返程中,我们亲历了一些恶劣情况。山谷风云突变,我们被浓雾所覆盖,细雨让公路变得泥泞不堪。我们在下坡路上时,开始下雪,公路变得又湿又滑,危机重重。我们花了长达八个小时才抵达河边的安全区——52 公里外的古拉布格尔(Gulabgarh)。如果当时没有离开,也许我们还会在天堂般的大山中超出预期多呆些时候。

公路变得又湿又滑,危机重重(图片来源:Himanshu Khagta)

The roads can become slippery and dangerous (Credit: Himanshu Khagta)

勇气可嘉的公交车司机会在这条单车道公路上往来(图片来源:Himanshu Khagta)

Daring bus drivers ply the one-lane route (Credit: Himanshu Khagta)

当地人已经对险峻的道路和环境习以为常(图片来源:Himanshu Khagta)

The people here are used to the treacherous roads and landscapes (Credit: Himanshu Khagta)

沿着旁吉至基斯赫特瓦尔公路会路过不同的小村庄(图片来源:Himanshu Khagta)

One encounters different villages along the Pangi via Kishtwar road (Credit: Himanshu Khagta)

为了在恶劣的环境中生存,人们要储备丰富的资源(图片来源:Himanshu Khagta)

The people are resourceful when it comes to weathering harsh conditions (Credit: Himanshu Khagta)

要花很长时间才走完 52 公里路程(图片来源:Himanshu Khagta)

A 52km stretch can take many hours to cover (Credit: Himanshu Khagta)

大雪会让旁吉山谷完全与世隔绝(图片来源:Himanshu Khagta)

Snowfall can leave the valley in complete isolation (Credit: Himanshu Khagta)

(责编:友义)

A perilous ride to a remote valley

By Himanshu Khagta,30 Apri 2024

Five of us packed into a car, allured by the promise of traversing one of India’s most breathtaking – and most dangerous – roads. The Pangi via Kishtwar road passes through two remote districts, Jammu and Kashmir, and connects the mythical valley of Pangi – hidden between the Pir Panjal range and the Zanskar range of the Western Himalayas – to the outside world when the regular route (via Saach Pass) is blocked due to snowfall.

In November, the weather is normally volatile. Snowfall can leave the Pangi valley in complete isolation for months. Yet, we were determined to make the trek. From one of India’s premier six-lane highways in the sprawling, northern commercial city of Chandigarh, the roads narrowed and we eventually began our two-day ascent along the former mule track. Now barely a one-lane dirt road, the route had been dynamited into the mountainside only a few years earlier.

Local lore has it that the people of Chamba, fleeing Mughal invaders, settled the hidden Pangi valley. Noble families would send their women and children to Pangi to live in peace and secrecy. When the valley later came under the rule of the Kingdom of Chamba in the 16th Century, officials posted here were given funeral allowance, since they were expected to never return home. According to another legend, the King of Chamba sent criminals to the valley to serve life sentences.

The Pangi via Kishtwar road cuts rights through mountain ledges, and for the most part, is only wide enough for one car at a time. Somehow though, brave bus and truck drivers ply the route too. If two cars meet each other going opposite directions, one driver has to carefully drive in reverse for potentially hundreds of metres until a suitable passing spot is reached. All along the road, cliffs shoot straight up to the tops of mountains, and then straight down thousands of metres to the rubble-strewn banks of the Chenab River. The road is so rocky and steep that one 30km stretch took us four hours to cross.

Along the way, we encountered locals who are used to the treacherous roads and landscapes that surround them. The Pangwal, descendants of the original settlers, have small agricultural farms along the route. And at higher altitudes, the Bhot people – who speak Tibetan languages and mostly make a livelihood herding animals – weather the harsh conditions by preserving meat, storing barley and brewing a type of hard liquor known locally as patru or rakh. Winter, when the whole valley is engulfed in snow, is the most difficult time for the locals. Reaching Chamba takes two days by road, and during medical emergencies, the government arranges helicopter service for the people.

On our descent back home, we experienced some of these harsh conditions first hand. Clouds rushed up the valley blanketing us in a thick fog, and a light drizzle turned the road into a slushy mess. And as we dropped in elevation, it was snowing, making the road even more slippery and dangerous. The 52km stretch to Gulabgarh – our safe zone near the river – took us eight hours to cover. Had we not left when we did, we might have spent much more time in that mountain paradise than we’d bargained for.