改变世界的十双鞋 - BBC阿拉斯戴尔·苏珂(Alastair Sooke)(2023年7月2日)

金凉鞋(Gold Sandal)(约公元前30 至公元后30)

鞋永远都是权力的象征,即便在古代亦是如此——就像这一双来自于罗马治下埃及、精致的镀金莎草拖鞋向我们所昭示的一般。这双鞋通体用金树叶装饰,是一件稀有的精致工艺品——但这双鞋几乎没有考虑到普通人的实际脚型。长期以来,出于各种理由,我们都有用鞋来束缚双脚的传统,而这双鞋正是这个传统的开始。鞋子经常能让穿它们的人感到异常疼痛。

(图片来源: V&A)

金莫哈利鞋(Mojari)(1790年-1820年)

这双华丽的男士莫哈利鞋(一种拖鞋),很可能来自于印度海德拉巴(Hyderabad)。与它相比,古埃及的镀金凉鞋就显得很普通。鞋子上部的皮革部分全部用金色刺绣装饰,鞋口则用金子和珍贵的宝石装饰,有钻石、绿宝石和红宝石。从这双鞋的贵重程度推测,它应该曾属于海德拉巴君主。无论谁是它曾经的主人,这个人一定是想通过这双鞋来向世人显示他无限的财富与权力。

(图片来源: Bata Shoe Museum)

红色芭蕾舞鞋(1948年)

鞋除了作为权利象征之外,同样也能成为幻想的标志。自古以来,它们都在民间音乐和童话中扮演重要角色:比如,当灰姑娘穿上水晶鞋,她就从女佣变成了公主。有一个版本的灰姑娘甚至可以追溯到公元前1世纪,故事涉及到当时的埃及统治者,一个希腊女奴隶和一个“穿鞋测试”(slipper test)。这双红色的芭蕾鞋,用绸缎和皮革做成,是为莫伊拉·希勒(Moira Shearer)出演迈克尔·鲍威尔(Michael Powell)和艾默力·皮斯伯格(Emeric Pressburger)1948年的电影《红菱艳》(The Red Shoes)时所制作,该片基于安徒生的童话故事改拍。

(图片来源: V&A)

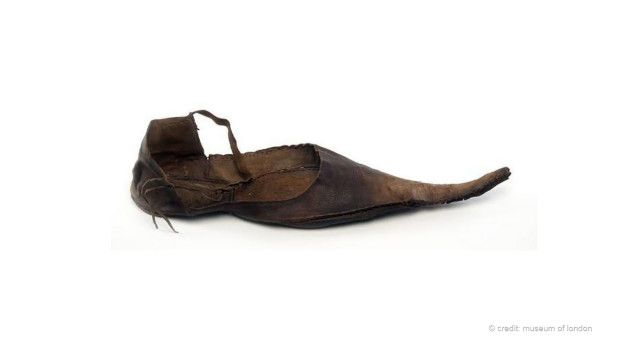

波兰那(Poulaine) (1375-1400)

中世纪欧洲的时尚达人不喜欢穿高跟鞋,他们更痴迷于细长型的、带尖尖鞋头的波兰那鞋。图片中的这双是用皮革制作的,应该是中产阶级穿的。朝臣们通常穿都用天鹅绒或绸缎制成的、不太实用的波兰那鞋。这种鞋在我们看来像是现代尖头鞋的鼻祖。对这种鞋的狂热,在14世纪晚期席卷了整个欧洲。当时这种鞋有多个名字,比如“克拉科”(来自Krakow)和“波兰那”(“优美”的法语发音)。鞋的尖头部分用苔藓填充以保持造型。为了便于行走,人们会将鞋尖向上弯曲。但是,应该几乎没人认为波兰那穿着舒服:中世纪的人一定抱怨过拇囊炎和锤状脚趾。

(图片来源: Museum of London)

土耳其木屐(19世纪)

从16世纪开始,在奥斯曼土耳其帝国,男人女人去浴室,或是去公共澡堂的时候,都会穿浴室木屐。每天去浴室曾经是生活的一部分,并且木屐一开始有一个很实际的作用:帮洗澡的人远离肮脏、湿滑、滚热的地面。渐渐地,实用性在时尚的圣坛前消失掉了。这一双19世纪埃及的木屐就是最好的证明,它具有难以置信的高跟。这双鞋高28.5厘米(11.22英寸),镶嵌了大量的贝壳和金属制品,使得它成为V&A博物馆鞋展上最高的一双鞋。

(图片来源: V&A)

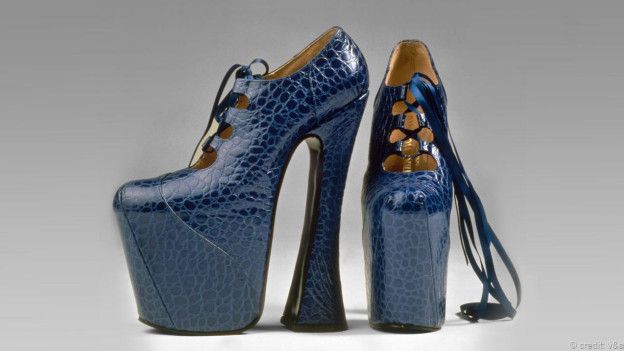

超高跟吉列鞋(1993年)

尽管奥斯曼土耳其木屐告诉我们利用鞋子增高并不是什么新鲜事,但有一双高跟鞋却最为臭名昭著:即,有着21厘米高跟的,由英国时装设计师薇薇安·韦斯特伍德设计的皮革加丝绸蓝色仿鳄鱼皮超高跟吉列鞋。1993年,超模娜奥米·坎贝尔在巴黎试装周上穿着这双鞋走在韦斯特伍德的T台之上。由于鞋实在太高了,让坎贝尔摔了一跤。在毫无征兆的情况下,其中一只鞋突然翻了个儿,使得坎贝尔跌倒在T台上。这是时尚界的一个标志性时刻,同时也是对那些为了追求外表的时尚而穿超高跟鞋的女性的一个警醒。

(图片来源: V&A)

布洛克牛皮鞋(1989年)

欲望都市的电视迷都知道,马诺洛·博拉尼克(Manolo Blahnik)的高级时装女鞋无比之昂贵。男士手工鞋也是如此:即便是简简单单的一双定制牛皮鞋也能高达3000英镑。这双布洛克鞋是由英国传统的衬衫和皮鞋制造商New & Lingwood制作的,用的是1786年的俄罗斯小牛皮革,它来自于当年在康沃尔(Cornwall)海岸附近的普利茅斯海湾沉没的瑞典商船。尽管这个皮革已经有上百年了,但一直用油布包裹着,所有依然可以用。制作一双如此奢侈的鞋,要经过200多道特殊工序,工艺非常复杂。

(图片来源: V&A)

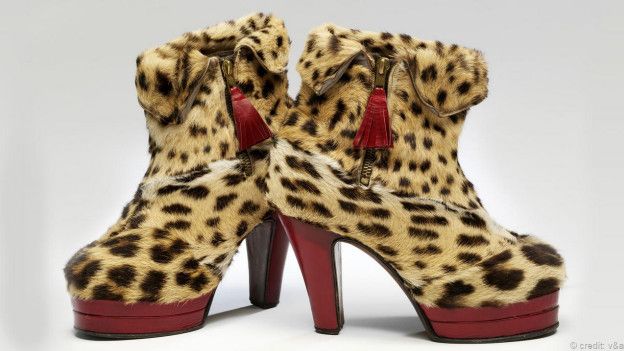

貂皮短筒靴(1943年)

有时候,不得已而为之的做法却能呈现奢华时尚的效果。这些短统靴是二战时期一位富人的,她把自己的一条水貂皮围巾和两件大衣给到肯辛顿(Kensington)当地的一个鞋匠,并让他用这些东西做一双鞋。这双鞋在物资需限量供应的战时显得格外引人注目。“这双鞋过于夺目、也过于奢华”,这次鞋展的策展人海伦·博森(Helen Persson)如是说,“但我认为这个故事最为精彩:这说明人们认为即使是在战争时期,拥有一些崭新而美丽的东西也非常重要。所以她才会用她的衣服换一双鞋子。如果我可以从这次展览上拿走任何一双鞋,我一定会拿走这双。”

(图片来源: V&A)

一双日式木屐(1880年至1900年)

鞋是引诱和欲望的必备武器。如马奈那副引起巨大争议的油画《奥利匹亚》中的那个妓女,全身赤裸,只剩脖子上的一条黑丝带和左脚上的一只高跟拖鞋(另一只早已经挑逗性的脱掉了)。在封建日本,高级妓女被称为“oiran”,穿的则是传统的木屐。像这双炫目的、天鹅绒红漆木屐,有20厘米(7.9英寸)高,有点像土耳其木屐、人字拖和恨天高的合体。当妓女穿上这种鞋,就必须保持迟缓、徐行的步态,交替的步子划出一个半圆——这样男子就能细细察看她们的美丽。

(图片来源: V&A)

伊梅尔达··马科斯(Imelda Marcos)的贝尔特拉米(Beltrami)凉鞋(1987年至1992年)

只要是有关鞋类的展览,一定会提到伊梅尔达··马科斯。她是前菲律宾总统费迪南德·马科斯·马科斯(Ferdinand Marcos)的遗孀,同时也是一位对鞋情有独钟、臭名昭著的购物狂。她生于1929年,她一生中收藏了约3000双鞋子,包括这双由意大利设计师贝尔特拉米制作的细高跟拖鞋,用了黑色刺绣和莱茵石作装饰。马科斯夫人会在她每一双凉鞋的鞋面签上自己的名字,这些鞋子现存于多伦多的贝塔鞋类博物馆(Toronto’s Bata Shoe Museum)。现在,“马科斯”代表的是很多人对鞋的痴迷情感,包括一些狂热的鞋类收藏者,所得之鞋并不用来穿,而是用来欣赏和赞叹。

(图片来源: V&A)

(责编:友义)

Ten shoes that changed the world - By Alastair Sooke

Gold Sandal (About 30 BC-AD 300)

Shoes have always been powerful status symbols, even in antiquity – as this delicate gilded papyrus sandal from Roman Egypt reminds us. Embellished with nearly pure gold leaf, it is a wonderfully slender and refined object – but it bears little relation to the actual physical shape of the average human foot. As a result, this elfin piece of footwear belongs at the beginning of a long tradition of shoes distorting our feet for one reason or another. Often, as well as pleasure, high-end shoes can cause their wearers extravagant pain. (Credit: V&A)

Gold Mojari (1790-1820)

This sumptuous pair of men’s “mojari” (mules), which were most likely made in Hyderabad in India, makes the gilded sandals from ancient Egypt look positively ordinary. The leather uppers have been entirely covered with gold embroidery, while the throats are decorated with gold designs embellished with precious gems including diamonds, emeralds and rubies. The quality of the construction is so high that they may once have belonged to the Nizam of Hyderabad – though it also appears that they were never worn. Whoever commissioned them wanted his feet to project an unambiguous statement about his seemingly limitless wealth and power. (Credit: Bata Shoe Museum)

Red Ballet Shoes (1948)

As well as attributes of power, shoes can also be objects of fantasy. Historically, they have played an important role in folk and fairy tales: when Cinderella’s foot fits the glass slipper, for instance, she is elevated from housemaid to princess. A version of the Cinderella story – involving the ruler of Egypt, a Greek slave girl and a “slipper test” – can be traced back to the 1st Century BC. These red ballet pumps, made out of silk satin and leather, were produced for Moira Shearer when she starred in Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1948 film The Red Shoes, which was loosely based on a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen. (Credit: V&A)

Poulaine (1375-1400)

During the Middle Ages, European fashionistas didn’t bother with high heels. Instead, they were obsessed with narrow shoes boasting long and unnaturally pointed toes, like this example made out of practical leather. Since courtiers were more likely to wear impractical versions made using velvets and satins, it probably belonged to someone middle-class. A craze for shoes like this, which to modern eyes look like precursors of the winkle-picker, swept the continent in the late 14th Century, when they acquired various names, including “crackows” (from Krakow) and “poulaines” (French for “Polish”). In order to keep their shape, the points were stuffed with moss. They were then curled upwards, to facilitate walking. Still, poulaines were hardly known for providing comfort: medieval wearers would have complained of bunions and hammer-toes. (Credit: Museum of London)

Bath Clogs (19th Century)

Beginning in the 16th Century, men and women visiting the hammam, or communal bathhouse, in the Ottoman Empire commonly wore bath clogs – or “qabaqib” in Arabic. A trip to the hammam was part of everyday life, and originally bath clogs had a practical function: they were designed to raise the bather above the hot, dirty, slippery floor. In time, though, practicality was sacrificed on the altar of fashion – as attested by this improbably tall pair of wooden qabaqib used in 19th Century Egypt. Lavishly decorated with shell and metal inlay, they are 28.5cm (11.22in) high, making them the tallest shoes in the V&A’s new exhibition, Shoes: Pleasure and Pain. They would have ensured that their affluent owner could elevate herself above her fellow bathers. (Credit: V&A)

Super Elevated Gillie Shoes (1993)

While Ottoman bath clogs suggest that using shoes to gain height is nothing new, one pair of high heels is more infamous than any other: British designer Vivienne Westwood’s leather-and-silk blue “mock-croc” Super Elevated Gillie platforms, with their 21cm-high heels. In 1993, the supermodel Naomi Campbell was wearing them on the catwalk during Westwood’s show in Paris Fashion Week, when they proved to be so lofty that they caused her to fall. Without warning, one of the shoes suddenly keeled over, sending Campbell tumbling to the floor of the catwalk. It was an iconic moment in fashion history – and a reminder of the extreme lengths to which some women will go in pursuit of appearing fashionable. (Credit: V&A)

Brogued Oxfords (1989)

As any Sex and the City fan will know, haute-couture shoes by the likes of Manolo Blahnik can be exorbitantly expensive. So can handmade shoes for men: even a relatively simple pair of bespoke Oxfords could cost more than £3,000. This pair of brogues was made by traditional British shirt and shoemaker New & Lingwood, using Russian calf leather salvaged from the wreck of a Danish ship sunk in Plymouth Sound off the coast of Cornwall in 1786. Even though the leather was hundreds of years old, it could still be used because it had been wrapped in oilskins. Constructing a pair of luxury shoes like this can be exceptionally complicated, involving more than 200 specialist steps. (Credit: V&A)

Furry Ankle Boots (1943)

Sometimes it is possible to achieve a luxurious high-fashion look with a make-do approach. These ankle boots were commissioned during World War Two by a well-to-do Londoner who took a mink stole and two coats – one made of red leather, the other from ocelot fur – to her local shoemaker in Kensington, and asked him to turn them into a new pair of shoes. The eye-catching results stood out in a period of wartime rationing. “They are a bit too flashy, a bit too high,” says Helen Persson, who has curated Shoes: Pleasure and Pain. “But I think that’s the most wonderful story: that in the middle of war it was still important to have something beautiful and new – so she came up with the idea of sacrificing her clothes. If I could take away any pair of shoes in the exhibition, it would be these.” (Credit: V&A)

Pair of Geta (1880-1900)

Shoes are an essential weapon in the armoury of seduction and desire. The prostitute in Manet’s scandalous oil painting Olympia (1863), for instance, is naked except for a black ribbon around her neck and one high-heeled mule on her left foot (the other mule has already provocatively slipped off). In feudal Japan, high-status courtesans called “oiran” wore traditional “geta” like this vertiginous velvet-and-lacquer pair, more than 20cm (7.9in) high, which resembles a hybrid between clogs, flip-flops and a skyscraper. The idea was that, while wearing them, prostitutes would be forced to adopt a slow, shuffling gait – alternately dragging their feet in a half-circle – so that their beauty could be scrutinised more easily by men. (Credit: V&A)

Imelda Marcos’s Beltrami Sandals (1987-92)

No exhibition about footwear could fail to mention Imelda Marcos, the widow of former Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos, who is a notorious shopaholic with a penchant for shoes. Born in 1929, over the course of her life she supposedly amassed a collection of some 3,000 pairs of shoes – including these sling-back high-heel sandals, decorated with black embroidery and rhinestones, which were made by the Italian designer Beltrami. Marcos signed the upper lining of each sandal in the pair, which now belongs to Toronto’s Bata Shoe Museum. Today Marcos embodies the obsession that shoes still engender in many people, including those passionate collectors who acquire footwear never to be worn, but only to be marvelled at. (Credit: V&A)