揭秘相扑手的真实生活 - BBC马修·布雷姆纳(Matthew Bremner)(2023年6月7日)

凌晨五点半,荒汐部屋相扑训练营,外面天寒地冻,里面相扑手正渐渐挣扎醒来,满脸睡眠不足造成的憔悴。一位年轻的力士(即相扑士)连哄带骗地想把酣睡的同伴弄醒,却被四处乱放的行军床和间或的几只手脚绊倒了。听到这名新弟子的动响,有的人费力地睁开睡意惺忪的双眼,有的却不加理会,全然不受影响地继续呼呼大睡。此时,等待着他们的是一场长达数小时的、在大阪郊区一废弃停车场进行的、令人骨头散架的训练。

为便于相扑手们参加三月大阪锦标赛(又称hon basho,是日本每年举办的六场相扑比赛中的一场),荒汐部屋暂时从东京老家搬到了大阪。在比赛前的一星期,我设法混进了相扑士的圈子,饶有兴致地见证了这项极为神秘的运动的日常现实。

大阪的都市天幕(图片来源: Yoshikazu Tsuno/Getty)

在费力地从床上挣扎起来后,力士洗漱并为训练做着装准备,包括梳理头发梳并将其盘成光滑的“丁髷”(丁髻)、以及在他们过度肥胖的腰身上系上三米长的“廻し”(缠腰布)。为了减缓新陈代谢并增进食欲,他们不吃早餐,在饥肠辘辘中开始了新的一天。

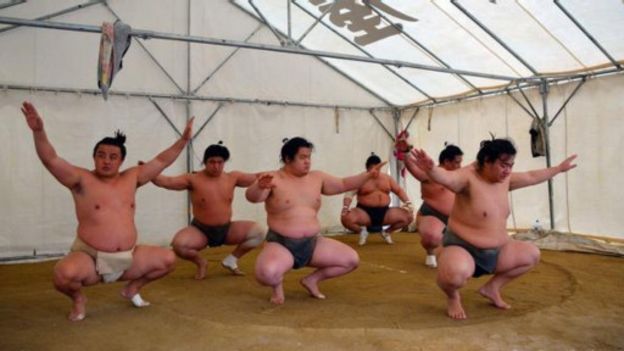

相扑手们一动起来,就像一艘艘舰船在惊涛骇浪里搏击航行。他们晃动身躯在颠簸中穿过一段狭窄的楼梯间,来到外面的小帐篷里。到那后,他们便开始着手准备土俵,相扑比赛将在这个神圣的圆环上举行。等清理干净粘土地板并正确标定该圆环的周长后,相扑手们包扎好旧伤上棉纱带,系紧有些松垮的腰布,活动筋骨,蓄势待发。他们从容闲适地弯身下腰、低到一个不可思议的高度,似乎身上的肥肉都柔软得与浸湿的粘土无异;这一瞬的优雅气质,足以让人不再认为他们大腹便便、行动笨拙。而这一切都在一种弥漫着浓烈的宗教仪式感的缄默中进行。

训练前准备土俵(图片来源:马修.布雷姆纳(Matthew Bremner))

相扑是一项富有精神气质的运动项目。历史学界公认,相扑的起源可以追溯到约公元3世纪的古坟时代。彼时,在神殿之上、在祭司等宗教人物面前表演的角力格斗,是宗教仪式的一部分。同样地,相扑中的许多做法均源自日本官方的宗教神道教。

自公元17世纪起,随着格斗比赛的意义转向为公共工程项目筹集资金,这些宗教仪式也过渡成了体育赛事。相扑摇身一变,成了一门生意;相扑手也变成了职业运动员。他们的名声随着以相扑著名赛事为主题的浮世绘的大卖而水涨船高,而日本民众则上瘾般地爱了这项本属于神道教的神秘的体育运动。渐渐地,相扑手身上实实在在的英雄气概使得抽象缥缈的神力黯然失色,而相较于过去旨在祈祷,相扑日益发展成为一种精彩的竞技表演。

拉伸运动结束后,相扑训练营的正式训练开始了。有的相扑手猛烈、不间断地上下托举杠铃,另一些则采用一种称为运足的蹲伏式站姿,双脚轮流向前滑动,快速穿过土俵。还有几个资历尚浅的新弟子开始做非常基本的相扑练习动作——四股。他们左右晃动,并进行一系列的踢蹬、深蹲、捶打、浅打。该项设计旨在增强相扑手的中枢肌肉力量,而且起码从象征意义上看,可以震慑恶鬼。

优雅而有力地移动(图片来源:马修.布雷姆纳)

相扑力士的日常训练似乎是出自本能的;从拉伸到四股,其就像一条河的流动一样无需思考与质疑。同样地,两位相扑手毋庸置疑地发现他们都站在了土俵之上,蓄势待发。他们面对面蹲踞着:他们微微点头,肌肉绷紧,神经高度紧张;不一会儿,两个圆滚滚的脊背就流满了汗水,时而抽搐,并不停转向;两条发热的腰带深深地陷进流沙般松弛的赘肉里。说时迟那时快,手腕一抖,未及任何的预兆,两位相扑手便全力扑向对方。霎时,气氛紧张到令人窒息,帐篷里回荡起了肥胖肉身大口喘气的声音。

强者对决(摄影:马修.布雷姆纳)

两人互相凿击、敲打、按压,直到有人失去平衡或者移出土俵。相扑手气喘吁吁,重新站好,拍了拍身上的灰尘,礼貌地向对手鞠躬致意。

相扑训练营级别最高的相扑手的到来后,大家向其表达出尤为突出的敬意。苍国来荣吉(Soukokurai)是一名中国籍蒙古族出身的相扑手。他是当今相扑界级别最高的相扑手之一,其比赛曾通过国家电视台转播给数以百万的观众。他甚至拥有自己的私人俱乐部。他体重140公斤,手似水桶,脸若圆盘,戴一条sekitori(一种高级别的相扑手)特有的整洁白色腹带,跋涉千里来到此地,却精神抖擞得像刚冲过凉一样,并在一个角落的位置站定。他的晚辈们怯怯地不好意思表达心头的敬意,他却并不以为愠,神情镇定。上场角力时,他表现出了与场外一样的从容镇定。当他年轻、浮躁的对手挥身上前,使出令人骨头散架的蛮力时,他一眼识破了他们的莽撞,平静地将对手引出土俵外。年轻的力士越是使出吃奶的力气,他反而越显得不费吹灰之力。

苍国来荣吉告诉我:“所有的年轻相扑手都希望成为sekitori,但是他们都没有资格与sekitori级别的相扑手对决。这就是为什么他们在训练当中都很想打败我的原因。”

大多数新进的相扑手都是15岁时便从高中辍学入会的。他们追求荣耀和财富,梦想过上sekitori的生活,拥有自己的粉丝俱乐部、堆积成山的奖金还有私人的随从仆人。然而他们发现,这种生活不过是疲倦和耻辱的结合,完全不值得羡慕。Sekitori确实可以不做家务、自由结婚,还可以住在训练营之外。但是,新弟子必须在每天训练很多小时的同时完成烹饪、清洁等工作,并满足高级相扑手的要求。

大约中午时分,力士们坐下开始吃午饭。寝室旁的房间里,十一位巨石般壮硕的相扑手盘腿围坐在一张低矮的餐桌旁。森严的等级制再次体现,高等级的相扑手才能首先进餐。

然而,大家的菜单却是相同的。相扑火锅(Chankonabe,力士们又称之为chanko)是这项运动的主要饮食,由肉汤、味醂(一种较淡的料理清酒)、白菜、鸡肉以及大量的各种精肉。每个相扑手一顿饭平均消耗6到10碗——大约10000卡路里。有一位退休的相扑手隆三杉太一曾被报道在一顿饭中吃了65碗相扑火锅而闻名于世。由于相扑运动是没有体重限制的,所以相扑手们总会努力增重,以在比赛中获得优势。

相扑手在一天漫长的训练结束后补充能量(摄影:马修.布雷姆纳)

房间里充满了此起彼伏的啜食声以及轻声细语的对话声。体重126公斤的21岁相扑手Goushi耐心地等力士的私人发型师“床山”为他梳起相扑丁髻。苍国来正在他身后接受媒体采访。在偶像面前,采访记者表现得非常笨拙紧张,说话结结巴巴。

盘起相扑丁髻(摄影:马修.布雷姆纳)

不一会儿,相扑训练营师傅铃木先生来了。这位前相扑手有着高大的身材和松弛的长脸,当他走进房间的时候,整个躯体仿佛正在下坠。然而,他凹陷的双目中有着一种无懈可击的庄重。相扑手们低头看着他们的锅,等待着这个必然降临的时刻。

“训练在三个小时后重新开始。大家休息一下。”铃木先生说道,太过于言简意赅,令人有些失望。

一秒钟之后,相扑手们开始慢吞吞地进食,竭力咽下最后一口难吃的食物。例行的训练又将开始,而惩罚也将继续进行。他们只期望未来能出人头地,让现在这一切都值得。

The life of a sumo wrestler - By Matthew Bremner

Haggard and heavy, the sumo wrestlers of the Arashio stable began to stir. A young rikishi (wrestler) stumbled over sprawling camp beds and stray limbs, coaxing his colleagues out of their deep slumbers. Some opened heavy eyes, while others batted away the young novice’s attempts and returned mulishly to sleep. It was 5:30 am and cold outside – and what awaited the wrestlers was hours of bone-crunching practice in an abandoned car park in the outskirts of Osaka.

The stable – where the rikishi live and train – had temporarily moved to Osaka from its Tokyo home, so the sumos could take part in one of six annual tournaments. I had managed to get access to the wrestlers in the week leading up to the March Osaka tournament, or hon basho, and was interested to view the daily realities of this secretive sport.

After heaving themselves out of bed the rikishi washed and dressed for practice, fixing their hair into slippery chonmage (topknots) and tying the 3m-long mawashi (loincloth) around their inordinate girths. They did not eat breakfast in order to slow down their metabolisms and increase their appetites, and began the day on the longing gurgles of their empty stomachs.

The wrestlers moved like a fleet of ships bashed between high waves, tossing and rolling their bodies down a narrow staircase and into the small marquee outside. There, they set about preparing the dohyo, the sacred circular ring in which the sumo bouts are held. After the clay floor was swept and the perimeters of the ring properly demarcated, the wrestlers nursed old wounds with tape, tightened saggy loincloths and began to stretch. They bent into improbable positions with an ease not unlike the fleshy suppleness of wet clay, and with a grace that negated the slosh and sway of their heavy paunches. One wrestler, whose vast shoulders swelled up the nape of his neck, sat nonchalantly, his thick legs splayed at 90-degree angles like a gargantuan banana skin. Another pressed his head deeply into his knees, his flanks rippling like a folded mattress. All this was done in silence, with the heavy air of a religious ceremony.

Sumo is a sport shrouded in spirituality. Historians agree that sumo dates back to the Tumulus period, around the 3rd Century, when fights were incorporated into rituals and performed on the sacred grounds of temples, in the presence of priests and other religious figures. As such, many of its practices derive from Shintoism, Japan’s official religion. Starting in the 17th Century, as matches were held to raise funds for public construction projects, these rituals transitioned into a sporting event. Sumo transformed into a business and the rikishi into professionals. The celebrity of the wrestlers grew in conjunction with the sale of woodblock prints featuring famous bouts, and the secret sport of Shinto became the opium of the Japanese masses. Little by little the tangible heroism of its wrestlers began to overshadow the abstract powers of the gods, and sumo became more a spectacle than a form of prayer.

After the stretching session, the stable began its training in earnest. Some wrestlers pumped weights in furious repetitions with equally furious grimaces, while others slid and scuttled across the dohyo in a crouched position called the suriashi. A few of the younger wrestlers started with the much parodied sumo manoeuvre, the shiko, in which the wrestler rocks from side to side in series of flailing legs, deep squats and dry, shallow slaps. This exercise is designed to increase the wrestler’s core strength and, symbolically at least, stamp out evil spirits.

Sumo is intensely traditional, where everything on display has a deeper meaning and where memories of the past are manifest in physical objects. The dohyo is representative of the sacred grounds of the shrines where sumo bouts were first fought; topknots are an ode to the hairstyles of the Samurai; and the referees, who dress in the guise of a Shinto priest, carry a dagger to signify the days when they would commit seppuku (ritual suicide) if they made an error during a contest.

The rikishi’s training routine seemed instinctive; from the stretching to the shiko, it was unquestioned, like the flow of a river. And in this same way, two wrestlers found themselves in the ring, ready to fight. They squatted opposite each other: two heads bobbing gently above clenched muscles and nervous tension; two round sweaty backs, twitching and turning; two chafing loincloths sinking deep into a quicksand of flab. Then, with no more warning than a flick of the wrist, the wrestlers threw themselves at each other and the deep suck of compressed air on loose flesh reverberated around the marquee.

Both men gouged, pounded and pulverised until one lost his balance and was barrelled out of the ring. Back on their feet and gasping for breath, the wrestlers dusted themselves off and politely bowed to one another. There was neither disappointment in loss nor smugness in victory, just a silent, respectful return to their positions.

This sense of respect was heightened with the arrival of the stable’s most senior wrestler. Soukokurai is Chinese of Mongolian descent, and one of the top ranked wrestlers in the sport, where his bouts broadcast to millions on national television. He even has his own fan club. Weighing 140kg, with hands like buckets and a face as flat as a plate, he waded into the marquee as if against a strong current of water and assumed a position in the corner. He wore the crisp white mawashiof a sekitori (a high ranked competitor), and looked on calmly, while his juniors were diffident in their respect. In the ring he wrestled with the same ease that he displayed outside of it. While his young, strident opponents flung themselves forward with bone-crunching crudeness, he collected their callowness calmly, and guided it out of the ring. The harder the young rikishi tried, the more relaxed he seemed to appear.

“All the young wrestlers want to be sekitori, but they don’t have the chance to fight a wrestler of that level in competition,” Soukokurai told me. “That’s why they have a lot of motivation to beat me in practice.”

Most new recruits are scouted at the age of 15, straight from high school, and come to sumo in search of glory and wealth. They want to live the life of a sekitori, with their own fan clubs, mountains of prize money and a retinue of servants. Yet, what they find is an unenviable combination of exhaustion and humiliation. The sekitori are exempt from many chores, are free to marry and live outside of the stable, but the novice rikishi are expected to cook, clean and tend to the needs of their seniors, as well as train many hours every day.

In between fighting, the wrestlers practise an exercise known as bukari-geiko, in which one wrestler throws himself at his ready companion and drives him from one side of the ring to the other, completing the exercise only when the inactive rikishi has been driven out of the dohyo. Once done, both wrestlers turn around and the inactive rikishi is driven back to where he came from. This drill is repeated approximately six times – each time the deadweight of the passive wrestler’s body getting heavier and heavier.

One of the younger wrestlers, exhausted after only his third repetition of the drill, struggled helplessly to push his much larger companion out of the ring. He bellowed and gasped, his fatigue turning into to lethargy and then slumping into concession. His muscles limp, his eyes shut, he seemed to cradle in the arms of his partner, all the momentum drained from his bulk. Around him, nobody moved or offered encouragement. The other wrestlers remained outside of the ring, continuing with their shikos and their stretching, indifferent to what was going on within in. For several minutes, the struggling wrestler just stayed there, as if asleep. His partner looked on askance.

Finally, unable to summon anymore energy the young rikishi gave up and walked out of the ring. Panting deeply, an indistinguishable grimace of tears and exhaustion scrunched on his face, he hid himself in one of the corners of the marquee and turned his back to his companions.

“The life of a young sumo is a tough one,” Soukokurai said. “You have to be patient, strong and disciplined, and if you’re all of those things, then maybe you’ll make it.”

The rest of the morning continued in a relentless musk of masculinity and the damp thwack of heavy flesh. The breathing got heavier, and bout after bout showed on the wrestlers’ bodies in burst skin, burning red slaps and deep black bruises. At around noon, their abundant flesh still aquiver from four hours of bruising bouts, the rikishi settled down to lunch: 11 brawny boulders sitting cross-legged around a low dining table in a room next to their sleeping quarters. Again hierarchy was enforced, the senior wrestlers eating first.

For both, however, the menu was the same. Chankonabe (or “chanko”, as the rikishi refer to it) is the staple meal of the sport. It is made out of a combination of dashi (broth), mirin(a weak form of sake), bok choy, chicken and a plethora of other brawny meats. The average wrestler consumes between six to 10 bowls per meal – around 10,000 calories – although the retired wrestler Takamisugi became famous when he reportedly ate 65 bowls of chankonabe in one sitting. Since there is no weight limit in the sport, competitors seek out advantage through sheer size.

The room was a cacophony of deep gurgling slurps and light conversation. Goushi, a 126kg, 21-year-old wrestler, sat patiently as a tokoyama, the rikishi’s personal hairdresser, tended to his topknot. Behind him, Soukokurai was being interviewed by the stable’s press agent, who fumbled and stuttered nervously in front of his hero. The rest of the rikishi, bending deeply into their bottomless bowls, concentrated only on their food; no conversation was worth more than what they had in front of them. And for a moment there was a sense of ease, of joviality and blitheness, where neither unbending tradition nor the prospect of training was imminently oppressive.

Then, Suzuki-san, the stable master, arrived. Tall, with the slack, drawn-out face of an ex-sumo wrestler, his whole body seemed to sag below him as he entered the room. Yet in his sunken eyes was a solemnity that countered any frailty in his appearance. The wrestlers looked down into their bowls and waited for the inevitable.

“Training starts again in three hours. Get some rest,” he said, too quickly for their liking.

The wrestlers lingered over their food for just a second longer, taking one last mouthful that didn’t taste so good now. The routine had returned and the punishment would continue. They could only hope that their future glory would make it all worthwhile.