每日一词:英语中有3,000个表达“喝醉”的单词

编辑:给力英语新闻 更新:2017年3月5日 作者:苏西·登特(Susie Dent)

一月戒酒(Dry January)才刚结束,那些"暂时"戒酒的人马上就恢复痛快豪饮的状态(on the booze)。"booze"(暴饮)这个词似乎带有一点蔑视的意味,还可能含有大量颓废的色彩。它听起来很摩登,但实际上已经有500年的历史,它由荷兰语中表示"过量饮酒"的"buizen"发展而来。该词最早出现在伊丽莎白时期的戏剧《粗鲁的接待》(Jack Drum's Entertainment)和一句很精辟的话中——"你需要痛饮一番"(You must needs bouze),那些在一月份以水代酒的人(hydropots)可能对这句话再认同不过了吧!

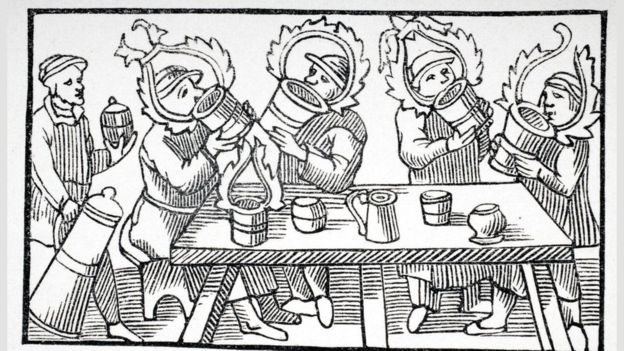

英语单词"booze"已有500年的历史,来自荷兰语"buizen"(图片来源:Alamy Stock Photo)

"Booze"曾在俚语和黑社会的行话中非常流行,这可能就是它现在带有一点叛逆意味的原因。一提到"酒精"(alcohol),在几个世纪里,英语"不辞辛劳"地创造出了大量正式和非正式的相关词汇。"alcohol"这个词本身已有800年的历史,起源于西班牙语种的阿拉伯语词汇"al-kuhul"(常用西班牙语中至少三分之一是阿拉伯语词汇,以Al开头的单词几乎都来源于阿拉伯语),该词的意思是"the kohl",即中东地区作为某种药用眼影的黑色细粉,与如今我们在化妆品柜台上看到的黑色眼影粉别无二致。而"the kohl"原本又是用来形容炼金术师通过蒸馏获得的粉末或精华物质,既包括用于脸上的药膏,也包括令人陶醉的蒸馏酒。

从那以后就有了"alcohol"这个词,并且深刻影响着我们的生活。在一千多年的时间里,烈酒供应商为酒创造出几百种新名词。过去人们很乐意来到当地的酒吧"勒欣顿的婴儿床"("the Lushington crib"),"沉醉之家"("shicker shop")或"狂欢大厅"("fuddle-caps hall"),品尝酒吧老板提供的美酒。这些酒吧老板也被人们戏称为快活的"小酒保"(knight of the spigot)。

"Booze"曾在俚语和黑社会的行话中非常流行(图片来源:Mary Evans Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo)

酒保们提供的调和酒使英语的词汇进一步丰富,有相对委婉的"tiger's milk"(老虎乳),也有明目张胆的诱惑"strip-me-naked"(脱光我)。如果将这些词添加到现代英语中3000个表示喝醉状态的词汇中(包括"ramsquaddled酩酊大醉","obfusticated迷醉","tight as a tick喝得烂醉"和比较奇特的"与理查德先生一起太自由了"("been too free with Sir Richard")等等),你会发现英语俚语中比它拥有更多表达方式的只有另外两类主题——金钱和性。

拥有如此丰富的表达,怎能让人整整一个月都不喝酒呢!而那些成功抵住诱惑的人可以安慰自己很高兴数周都没有"crapulent喝多","cropsick喝醉"或"wamble-cropped喝吐"的不良感受,这是三个充分表达宿醉的词。

过去,前一天晚上酗酒的人会在早上醒来后选择比较极端的醒酒方法,有些人用螃蟹烧成的灰,还有些人喝醋,有钱人则会在喝酒之前往杯子里加一块紫水晶(amethyst)。"Amethyst"一词源于古希腊语中的"amethustos",意思是"喝不醉",这种石头曾被人认为拥有防止人喝醉的魔力。

英语有3000个表达喝醉的词,其中包含"ramsquaddled 酩酊大醉"和"obfusticated 迷醉"(图片来源:Alamy Stock Photo)

以前,"hair of the dog (that bit you)"这个短语完全可以根据字面意思来理解:拔下(咬你的)狗头上的一撮毛。在中世纪时期,被流浪狗咬了一口的人会追着狗跑,直到扯下狗头上的一撮毛才罢休,据说这撮毛做成的药膏可以很好地缓解酒后忧郁的情绪(在德国,人们把这种感受称作"Katzenjammer宿醉",把人们喝醉后的呻吟比作猫的哀嚎)。"poison"(毒药)这个词很有可能起源于拉丁语中表示"喝酒"的词"potare"。

"烂醉如泥"

禁酒运动期间,政府鼓励民众接受绝对禁酒主义(tee-totallism)。"tee-totallism"一词中的"tee"是为了强调"Total"第一个字母"T"的发音。当时,戒酒的人们发誓即使酒瘾难熬,也不会破戒,宁愿面带微笑爬到马车上喝水,这里的马车(the wagon)就是指禁酒运动期间往美国小镇上运水的车辆。于是,on the wagon就指"戒酒"了。

在德国,人们把酒后忧郁称作"Katzenjammer 宿醉",把人们喝醉后的呻吟比作猫的哀嚎。

禁酒运动很快就传到了英国,使得人们在戒酒和"喝得烂醉"(drunk as a lord)之间挣扎。"drunk as a lord"是17世纪的一个短语,与骂人的粗话"bloody"奇怪地联系在了一起。"Bloody"被认为是起源于同时期的纨绔子弟或贵族流氓,"像纨绔子弟一样喝醉"(bloody drunk)意思是"喝得烂醉"(drunk as a blood),换句话说,就是像有钱的流氓那样喝醉了。这些纨绔子弟喜欢的事情中,好像没有什么能比得上"将镇子涂成红色"("paint the town red"),这又是一个与喝酒有关的短语。人们认为英国中东部城市莱切斯特附近的小镇梅尔顿莫布雷(Melton Mowbray )就是短语中所说的小镇(town),一天夜里,镇上沃特福德的侯爵们和一帮朋友喝醉后放纵狂欢,提着几桶红色颜料将镇子涂成红色,因此paint the town red就指"醉酒狂欢"。

虽然参与一月戒酒的人会直接避免喝得大醉,但如果说得更加隐晦些,就很难不喝醉了,因为英语中有很多难以想象的词汇来替你掩盖在一月戒酒时喝醉的事实。比如,形容词"bridal"("婚礼的")来源于"bride-ale"("新娘啤酒"),用来形容酒水丰盛的喜宴。另外,"small beer"是一种被重度稀释后酒精含量很低的啤酒,在喝酒比喝水适合的场合,儿童和成人都可以喝。

现在,我们都很喜欢在社交媒体上嘲讽(lampoon)政客。"lampoon"这个词也与喝酒有关。对法国人来说,"Lampons!"指"喝!",常用来劝喝酒的人举起酒杯,唱一两首歌。由于唱的歌通常是嘲弄和讽刺性的,所以"lampoon"在现代就有了"讥讽"的含义。"Lampooning"和"carousing"经常连在一起用,"carouse"来自德语"gar aus trinken",指"一饮而尽"。

美国的禁酒运动期间,人们被鼓励接受"绝对禁酒主义"。(图片来源:Alamy)

还有一个更出乎意料的词。我们现在可能会说"pissed as a newt"( 表面意思是"醉得像蝾螈"),但罗马人会说"drunk as a thrush"(表面意思是"醉得像画眉"),就像画眉吃了发酵的葡萄之后欢快地在葡萄园里东倒西歪的情景。奇怪的是,英语中的单词"sturdy"却可能来源于拉丁语中表示画眉的单词"turdus"。在13世纪, "sturdy"指人故意作出鲁莽的行为,还有可能形容人像喝醉的鸟一样一动不动。

鸟儿、蝾螈和有教养的贵族都一样——难以抵挡醉酒(groggy)的诱惑。尤其如果你是一名爱喝朗姆酒的水手,就更是如此了。"groggy"这个词来源于公海之上,这还多亏了英国海军上将爱德华·弗农(Edward Vernon)。由于他身上的外套是粗布(grogram)制成,很厚很粗糙,人称"Old Grog"。这个绰号的由来还有另一个故事,弗农下令,朗姆酒要用水稀释后再定额供给的水手们,引得大家很是不满。grog这个词有"掺水烈酒"的意思,大家也因此叫他"Old Grog"。所以,水手们之间的行话出现了两个与他有关的表达肯定不是弗农自己批准的。

弗朗西斯·格罗斯( Francis Grose)在1785年编纂的《经典俗语词典》(Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongueas)中,将"An Admiral of the Narrow Seas"(狭海的海军上将)定义为"喝醉之后吐到坐在对面的人的衣服上的人"(更糟糕的是,"狭海的海军副将"指"喝醉后躲在桌子下面往别人鞋子里撒尿的人")。而那些喜欢乱扔啤酒杯、还津津有味地喝酒的人从一开始就被称为"tosspots"(酒徒)很可能也是有原因的。

不管你是"Tosspot"还是"hydropot",都可以在英语中找到你的故事。如果一品脱的发泡燕麦酒或一杯诱人的红酒正在向你招手,那么就来干杯吧!别忘了加上紫水晶哦!

Dry January is almost over, and temporary teetotallers everywhere will soon be back on the booze. That word ‘booze’ tends to conjure up a certain amount of slurring, with perhaps a swig of decadence thrown in. It also sounds distinctly modern. It is, in fact, over five centuries old, having slipped into English from the Dutch word buizen, to drink to excess. It gets an early mention in the Elizabethan play Jack Drum’s Entertainmentand the pithy statement ‘You must needs bouze’ - a sentiment with which few of January’s hydropots (one term for water-drinkers) would disagree.

‘Booze’ was once a popular term in the slang or ‘cant’ of the criminal underworld, which may explain its rebellious overtones today. But whether formally or informally, when it comes to alcohol, English has been hard at work for centuries. ‘Alcohol’ itself is 800 years old, taken from the Spanish Arabic al-kuhul which meant ‘the kohl’, linking it with the same black eye cosmetic you’ll find on any modern make-up counter. The term was originally applied to powders or essences obtained by alchemists through the process of distillation. This included both unguents for the face as well as liquid spirits of the intoxicating kind.

The only subjects that fill the pages of English slang more are money and sex

The heady result has been with us ever since. Purveyors of the strong stuff have invited hundreds of epithets over a millennium or more. Drinkers of the past would happily visit ‘the Lushington crib’, ‘shicker shop’, or ‘fuddle-caps hall’ (ie the local pub) to sample the offerings of the landlord - aka the jolly ‘knight of the spigot’.

The concoctions those knights dispensed fill an even richer lexicon, veering from the euphemistic ‘tiger’s milk’ to the blatant invitation of ‘strip-me-naked’. Add those to the 3,000 words English currently holds for the state of being drunk (including ‘ramsquaddled’, ‘obfusticated’, ‘tight as a tick’, and the curious ‘been too free with Sir Richard’) and you’ll find that the only subjects that fill the pages of English slang more are money and sex.

Such a lush lexicon makes it all the harder to forsake alcohol for a whole month. Those who’ve made it, however, can console themselves with the fact that they have enjoyed weeks without the unpleasantness of feeling ‘crapulent’, ‘cropsick’, or ‘wamble-cropped’: three beautifully expressive words for the dreaded hangover.

In days gone by, drinkers opted for extreme cure-alls for the morning after the night before, from the ashes of a crab to the drinking of vinegar, although the wealthier might have preferred dropping an amethyst into their glass before imbibing. ‘Amethyst’ itself came to the language from the Ancient Greek amethustos, which means ‘not drunken’, because the stone was once believed to hold magical properties that prevented intoxication.

Meanwhile, the idea of having a ‘hair of the dog (that bit you)’ was once entirely literal. In the Middle Ages, anyone bitten by a stray dog would run after the offending animal in an attempt to pluck out one of its hairs: a poultice with that hair was believed to greatly ease the post-drinking blues (what in German they call a Katzenjammer, in which the drinker’s moans are compared to the wailing of a very miserable cat). It is probably entirely appropriate that the word ‘poison’ is rooted in the Latin potare, to drink.

‘Drunk as a thrush’

Those on the wagon can afford a smug smile over shenanigans like these. The wagon in question originally carried water around small town America during the temperance movement, when citizens were urged to embrace ‘tee-totallism’, in which the ‘tee’ was there simply to give emphasis to the first letter of Total.

The idea soon crossed to Britain, where abstinence battled with the thrill of being ‘drunk as a lord’, an expression from the 17th Century that’s curiously linked to the swear-word ‘bloody’. The expletive is thought to have begun with the ‘bloods’ or aristocratic rowdies of the same period, when to be ‘bloody drunk’ was to be as ‘drunk as a blood’ – in other words, as sloshed as a posh hooligan. There was, it seems, nothing these bloods liked more than painting the town red, another phrase in the drinking arsenal that the town of Melton Mowbray near Leicester in the East Midlands of England has claimed for its own, thanks to a night when the Marquis of Waterford and a group of friends ran riot with pots of scarlet paint.

The adjective ‘bridal’ began as ‘bride-ale’, and was used of a wedding feast that featured plenty of the strong stuff

For all that partakers in dry January have avoided such results of befuddlement directly, it would be hard to do so with their more metaphorical tongues, for drinking is behind a surprising number of words that have since hidden their tipsy history. The adjective ‘bridal’ began as ‘bride-ale’, and was used of a wedding feast that featured plenty of the strong stuff. ‘Small beer’, on the other hand, was a heavily watered-down version of the original, enjoyed by both children and adults when drinking water could prove a lot more perilous than ale.

While we like nothing better than lampooning politicians on social media these days, that word too has its roots in guzzling. ‘Lampons!’, for the French, meant ‘let us drink!’, and was an exhortation to merry revellers to pick up their glasses and sing a song or two. As those songs tended to be mocking and satirical, so our modern sense of ridicule crept in. Lampooning and carousing went together – appropriately enough given that ‘carouse’ is from the German gar aus trinken, meaning ‘drink to the bottom of the glass’.

There’s an even more surprising word to add to this list. We may be ‘pissed as a newt’ these days, but for the Romans the image of choice would be ‘drunk as a thrush’, an allusion it seems to the bird’s merry tottering around vineyards after feasting on fermented grapes. Bizarrely, our English word ‘sturdy’ may go back to the Latin turdus, thrush. Anyone described as ‘sturdy’ in the 1200s was wilfully reckless and possibly as immovable as a sozzled bird.

Birds do it, newts do it, even educated lords do it: the pull of getting groggy seems hard to resist. Especially if you’re a sailor, whose associations with rum are legendary. Fittingly, ‘groggy’ itself was born on the high seas thanks to the English naval officer Admiral Edward Vernon, nicknamed Old Grog on account of his thick coat made of coarse grogram cloth. It was Vernon who gave the unhappy order that his sailors’ rations of rum should be diluted with water. He surely would not, then, have approved of two expressions that emerged in the sailors’ slang of his day.

An Admiral of the Narrow Seas is defined in Francis Grose’s 1785 Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongueas “one who from drunkenness vomits into the lap of the person sitting opposite him”. (Worse still, a Vice-Admiral of those same seas is ‘a drunken man that pisses under the table into his companion’s shoes’.) Not for nothing, perhaps, were those who liked to throw back their mug of beer and drink its contents with relish known as ‘tosspots’ from the start.